- Home

- Oana Aristide

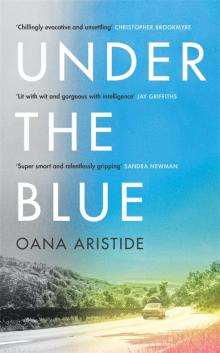

Under the Blue

Under the Blue Read online

MORE PRAISE FOR UNDER THE BLUE

‘A super-smart and relentlessly gripping addition to the ecofiction genre, Under the Blue is by turns chilling, incisive and casually hilarious. It also features one of the most convincing sentient-AI characters in recent fiction’

Sandra Newman, author of The Heavens

‘Terrifying but hopeful, smart, vital and urgent: the ultimate must-read’

Charles Foster, author of Being a Beast

‘What an extraordinary book this is; ostensibly a compelling, addictive post-apocalyptic thriller, but also a ferociously intelligent examination of artificial intelligence, a highly accomplished treatise on the function of art and a lyrical, moving, vitally urgent plea for expanded ecological awareness’

Niall Griffiths, author of Broken Ghost

‘A clear-eyed, unstinting challenge to all our complacencies that is unsettling, brave, philosophical and as fast-paced as a thriller. A Frankenstein for modern times that just might be the book to change our lives’

Laura Beatty, author of Lost Property

Under the Blue

OANA ARISTIDE

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Serpent’s Tail,

an imprint of PROFILE BOOKS LTD

29 Cloth Fair

London

EC1A 7JQ

www.serpentstail.com

Copyright © Oana Aristide, 2021

Cover Images © iStock

Cover Design: Steve Panton

Lyrics from ‘Wish You Were Here’ (p. 14) © David Gilmour and Roger Waters, 1975. Reproduced by kind permission of Hal Leonard Europe.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, dead or alive, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library

ISBN: 9781788165839

Export ISBN: 9781788167611

eISBN: 9781782837350

To Binga

Part One

1

July 2020

London

He has won another lottery. One hundred pounds on a green scratch card, and that’s with the bonus field still to go. He would like to share this moment with someone, and he looks up, but there’s only the TV in a corner of the living room. The woman newsreader has almond eyes and heavy L’s: plump, woollens on a clothesline. Slavic L’s. The screen switches to shaky phone-camera footage of human bodies strewn across a courtyard.

He scratches the bonus field.

He doesn’t double the hundred, but it’s fine. What matters is that he wins more often than the statistics predict. Happy as a kid each time, and it’s not about the money. Is it the knowledge that someone does win, that the whole thing’s not rigged? Sometimes, late at night, content and in a sleepy torpor, he’s tried to explain to whoever was lying next to him that it’s about having faith in the world, in things being true and good.

The Slavic newsreader is back, talking about mass poisoning. They seem to think it was mushrooms. In the BBC studio, a guest shakes his head, says subsistence agriculture, and opens his arms, palms upwards.

Until last autumn, he’d not had a TV set for thirty years. This one was already in Tim’s flat and stuck to the wall when he moved in. He worries he has forgotten how to watch TV. He is impatient, distrustful of narratives. Plot points pass him by. The frenzied banners, insistent and red, only stir him to wilful indifference. Instead, he picks up disjointed facts, random words, bizarre and mysterious images that months later turn up in the corners of his paintings.

Downstairs, the building’s recycling bins are full not of beer cans and wine bottles, but of flattened cardboard boxes. He is curious, stops with his empty bottles when no one’s around and turns the cartons this way and that, wonders at the contraptions depicted on them. Juicers, blenders, exercise bikes, vacuum cookers and squat little plastic barrels of protein powder. Endless cartons of coconut water. His neighbours, he suspects, are serious about putting up a fight.

He doesn’t belong in this place.

He learned that he’d inherited the flat a few weeks after Tim’s accident. By then, he was wallowing in guilt. Tim had been thirty-two at the time, and worked for a hedge fund, yet now Harry could only think of his nephew as a thin, shy boy who liked to stand holding his elbow. Then the flat came along, two bedrooms in a shiny new development with twenty-four-hour concierge service. The place where Tim had lived for the past two years. The easiest thing, the sensible thing, would have been to sell.

There’s constant traffic of dry-cleaned shirts and Amazon parcels at reception. Everyone has real jobs that they actually go to, so that Monday to Friday, during the day, the building belongs to him and the cleaning ladies. The flat has low ceilings and small windows. It’s terrible for painting. The walls are thin. When his neighbours are at home it sounds as though they are many, entire hordes of them, but when they appear on the landing it can be just one little Japanese woman eyeing him accusingly. Does he sound like many, too?

Customers and gallery owners don’t like his new place. It’s not arty, and it’s not ironically not arty. Inside, he has to invite them to step closer to the paintings, lure their glance away from the plasticky vertical blinds.

He makes enemies, and friends. The concierge stops him one day at reception, tells him ‘a third party’ has complained of his flat smelling of turps. ‘Fire hazard, sir. Very serious.’ The man points a pen at the fine print on an A4; Harry guesses it’s the terms of the lease contract. He is caught off-guard by this reprimand, hesitates between denying the charge and rejecting the man’s authority in the matter, when the young woman who lives opposite appears at the desk. ‘It’s just the vents. They’re weird in this place,’ she tells the concierge. ‘I can smell the neighbour’s perfume in the morning when she gets ready for work. Perfume is flammable. Is that a fire hazard?’

The concierge beats a retreat; he doesn’t want to deal with anyone’s perfume. The young woman heads for the lift. Harry catches up with her, thanks her, informs her it’s not even the turpentine people should worry about, but the oily paint rags and their potential for self-combustion. ‘Oh well. Worse things could happen’ – she smiles – ‘than burning for art.’ He’s smitten.

He doesn’t know her name. They’re not known by names here, that’s another thing. By decree of the concierges, they’re all flat numbers. Miss Twenty-Two and he now and again share the lift, so each time he has about thirty seconds to talk to her. She’s small and dark, with short hair and unusual, alarming deep-blue eyes. A hint of a foreign accent. She’s vague about where she works. He guesses that she’s unhappy with her job, and likes her more for it. If she ever knew Tim, she doesn’t let on. He has a feeling she would understand if he explained himself to her. I’m honouring the memory of my dead nephew. Penitence; these continental types would get it.

When he has doubts about living and working there, he tells himself that all the things that are bad for painting are good for art.

The only change he’s made to the decor of the flat is the large self-portrait he hung up in the living room. Oil on canvas, his face flatteringly unkempt, intense eyes issuing some unspecified challenge. Streaks of moss green through the shock of hair, wilder than his own grey. His frame hulking rather than overweight. It’s a painting he could

have sold a hundred times over.

Lately, the fingers of his left hand have taken to moving of their own accord. Several times, when resting or deep in thought, he has caught them moving as though caressing something. His father used to do the exact same thing in his latter years. Now why would you, he wants to ask his hand, take up an old man’s tic?

He could tell his young neighbour that by living in Tim’s flat he hopes to produce a work of art that somehow embodies Tim. That he means to achieve nothing less than a small resurrection. That this plan is hampered by the fact that he didn’t quite know the boy, and still doesn’t, even though he has letters, photos and bank statements, almost everything a biographer could ask for. That he has never felt less confident about a project, and that several times he turned the flat upside down looking for stuff to add to his archive: more photos, more letters. Where’s the boy’s driver’s licence?

But they stick to small talk. She sees him carry canvases out of the flat and asks him about his work. He tells her about his cottage in Devon, which he abandoned in order to move here. He exaggerates its charms, turns businessy farmland into a bucolic paradise. He anthropomorphises the sheep, and sheepifies the farmers. When she professes a love for nature, he casually offers her the use of his cottage for a weekend. You’ll like it. On clear nights, you can see the Milky Way.

What do they make of him, his young neighbours? A lonely man with paint-stained hands and an invisible burden.

He teaches drawing once a week, finds himself repeating clichés. Walk before you run. He tells students who want to capture sentiments and ideas right away that a basic sense of proportion is the most important thing. Noses before souls, he improvises, neglects to add that no one can teach a hand a sense of proportion.

On TV they’re showing the grainy Russian news clip again, then a gaggle of cartoonish figures in yellow hazmat suits in a hospital. On a beach; in a car park. Yellow, boxy humanoids have overrun the unlucky lands of the news.

One day, he uses his thirty seconds in the lift to tell his blue-eyed neighbour that blue pigment used to be made from semi-precious stones, and that it was the most expensive colour. Ultramarine, they called it. A colour that signified power and wealth, or heavenly status. He tells her that when scientists eventually learned to produce the colour artificially, the compound was called Prussian Blue, and that it was a type of cyanide, but also an antidote to a whole raft of illnesses: both a poison and a cure. That as an oil colour it is one of the slowest to dry; yes, colours dry at different rates.

‘Blue is demanding. Blue,’ he sighs, ‘gives me grey hairs.’

He tells it to her exactly like this, hotchpotch, to get it all out before the ping of the fifth floor. She smiles. She’s flattered. She knows what he’s up to, and when she leaves the lift it’s with a look of complicit amusement.

At his age he has still not conquered distraction.

He suspects he’s not a great artist. He overworks. Painting, to him, is like driving along a poorly signposted road for weeks on end, every so often wondering if he hasn’t missed his turn. It’s a cruel joke that he recognises an overworked painting right after it’s irredeemably overworked. This thought, that he’s not much of a painter, provokes a deep disquiet, and over the years he’s built a wall around it, so that mostly it’s just there, lurking in the background, like the temple of a malicious deity.

He worries about the lies he may have accidentally told himself.

The other day at the reception desk he overheard a young man flirting with Twenty-Two. The fellow did it in a very forward way, no finesse at all, and instead of playing along, she actually, visibly, winced. Harry was so pleased he was still smiling about it in the evening.

He is grateful for small mercies.

Why did Tim have a second bedroom? A young single man, still at the start of his career, why would he spend a fortune on a two-bedroom flat? The second, smaller bedroom, still in waiting mode when Tim died: a metal bed frame with a new, bare mattress, a dirty laundry basket in a corner, and nothing else. Was Tim seeing someone when he bought the flat, and what does the unused second bedroom mean in that case?

The bed frame and mattress are up against the wall now. Still in waiting mode: he means to give them to some charity that will come and collect. He has turned the room into a studio. It’s a permanent mess; he paints by stapling a large canvas on to plywood boards that he has nailed to the walls. This makes it possible to eventually cut out a part of the work that he feels good about and abandon the rest.

He paints in bursts. ‘Deep-dives’, he calls them, and though he knows he’ll be painting for days, sometimes for weeks, he’s always in a panic at first. Often he wants to work on a dark background, and he’ll splatter the black on the canvas in a frenzy, like a madman, only to then sit by, anxiously, having to wait for the paint to dry. Dying to start making light. Sometimes he receives a text message cancelling his Wednesday classes, and then he’ll not leave the flat for a week. He eats carelessly, whenever he remembers hunger, pasta with butter if that’s all there’s left. At night he dreams of otherworldly paintings, tumbles along sinuous canyons of dried paint. Wakes up struggling to retrieve from the dream those new colours, the impossible shapes.

He is more careful now about his empty bottles. He keeps them away from the front door, invisible to anyone happening to look in, and he takes them to the bins between nine and five, when Twenty-Two is at work.

It could be that he drinks too much.

It’s always something extraneous that jolts him out of the deep-dive. This morning it’s a power cut. The kettle won’t boil water, the bathroom light doesn’t come on. He’s red-eyed, pickled in turpentine, and with colour pigments in the folds of his skin. He races past the deserted reception, glad not to have to interact with anyone yet. On days like these he feels like a soldier out of the trenches. Raw down to the inside of his ears, and on edge: out on the street a sudden human voice, a car horn, might well make him vibrate, might trigger some final and mysterious expression.

He has dressed without thinking, only belatedly remembering the bright sun outside. The lining of his mackintosh clings to the back of his neck, and he takes care where he steps: he can’t see any dog shit, but he smells dog shit. He also smells rats, or squirrels, dead and rotting in the bushes by the canal, and the deceptive lawn of bright green scum covering the canal itself.

The world is new and strange.

He walks towards Upper Street, meaning to buy food, but sometimes, when he’s in this raw and receptive state, an idea will come to him, insistent, unpostponable, and he will have to scurry back to his flat and grab hold of a brush.

He’d like to know what Tim made of art.

There are fourteen pubs within a one-mile radius of his building, and he’s been round all of them, showing the bartenders photos of Tim, trying to find out if the boy used to be a regular. The bartenders are either suspicious, think he’s the police, or they look at him bemused, pointing at the inevitable throng around the bar. Now how would I remember anyone?

He knows his new neighbourhood by now. He knows local opening hours, and that the number 4 bus takes a very long way round. Before visiting the gallery in Holloway he always checks Arsenal’s match-day schedule online. A few months ago, drunk, happy fans tried to tip over his bus. They only gave it a shove, but from the top it felt as though the bus might really roll over; he was afraid. He felt old and helpless.

He suffers from sudden insights. The latest: it’s impossible not to be ridiculous.

The open street is overwhelming after a long painting session. When he finds the Sainsbury’s closed, he hovers in front of the entrance, wallet in hand. A vagrant appears from behind a corner, asks, ‘What’s goin’ on, mate?’ Several grubby coats and sweaters are tied around the man’s waist, trailing behind him like the train of a gown. Madness in his eyes, a horrendous smell. ‘You know, don’t you? Where’s everyone gone?’ The man reaches out to grab him, and Harry flees, rushes p

ast other shops, all closed. It must be a bank holiday he has missed. It wouldn’t be the first time.

He hasn’t spoken a word in days.

Even out in the street, his mind is still entangled in the painting. Every idea he has, it’s like a prayer: nothing in itself, absolutely nothing. Thousands of flat and dead brushstrokes, yet sometimes, out of that nowhere, one brushstroke brings a work to life. A hint of defiance in the tilt of the head. A shaft of light that darkens. Then he covers everything except that one true line, and starts over.

He’s not there yet.

He passes a council estate on his way back to the flat, and on a balcony there’s a thin old man leaning over the railing, coughing. His mouth is open so wide it looks as though his jaw has come unhinged. A burqa-covered woman is trying to coax the man back indoors. This image of illness and old age brings to mind all the statistics that condemn him, too: his girth, his weight, his blood pressure, his alcohol units, his cholesterol, his salt intake, his pitiful genetic inheritance.

Sooner or later he’s going to need another lottery win, another victory over statistics.

There are no children in his building, and nobody cooks. In the evenings, the smell of weed wafts over from the flats beyond the canal, but in the actual building, nobody smokes. At any one time no more than a quarter of the underground parking spaces are occupied: it seems that hardly any young Londoners drive. When he’s in the communal spaces he feels like a detective, adding this strange piece and that to a puzzle that has no reference picture or borders. He wonders if his neighbours, too, are working away at their puzzle of him, if they have smelled the turpentine fumes escaping his flat for the past few weeks, and fully expect a large rectangle wrapped in glassine paper to follow.

This past year, he realises, it’s as though his life has been put on pause. A year that could be a painting, only hinting at movement.

He’s back in front of the canvas. It’s a life-sized portrait of Tim, the image that has stuck in his memory: the gangly, shy boy in jeans and a navy hoodie, his eyes partly covered by hair, left hand holding his right elbow. The way Tim appeared in his parents’ garden, to tell them he was taking off for ‘a game’. Awkward and terse because he was like that, or because friends of his were waiting on their bikes by the fence? And what kind of game? He never asked. Ball sports, or computers?

Under the Blue

Under the Blue